Mumford Holland was a close family friend of the Renfrows. A long time neighbor, they cared for him in his final years, and he left his property to members of the family. His story was told in the Hazelwood Cemetery Walk in September 2023.

“When I think about Mr. Holland – who lived and was still independent, vibrant, going out on his own – at 108, I think about the wonderful Mrs. Edith Renfrow Smith who is alive at 109. Her mother, Eva Pearl Renfrow was intentional and adamant about making sure her children got an education, were self-sufficient, and confident in themselves. I’m sure she expressed this sentiment to Mr. Holland. He played a huge hand in influencing and contributing to their future, including them moving into his house. He would have known the four oldest Renfrow children, who were 12, 10, 9, and 7, at the time of his death. He would have been around when Edith Renfrow was born. I would pose to you this vision that I like to come back to: Mr. Holland holding two year old Edith Renfrow, imagining a radically different future for her, a future where she grew up and excelled in her elementary and high school education, where she graduated from one of the most prestigious colleges in the country, where she got married and had two daughters, where she built a beautiful life for herself in Chicago. Where a state-of-the-art building would bear her family name in honor of her remarkable legacy. If only he could see her now.”

From the narration to honor Mumford Holland during the Grinnell Historical Museum Hazelwood Cemetery Walk, September 23, 2023. Written by Libby Eggert, Grinnell College Class of 2025.

Today’s post is not focused on the book process, but about broadening the understanding of why this story is so important to tell and how deeply tied Edith Renfrow Smith is to the community of Grinnell.

Yesterday I had the pleasure of presenting stories of African Americans of Early Grinnell with other members of a group who researched the subject over the summer of 2023. I worked with three students and Professor Tamara Beauboeuf to add to what is known and included in the local archives on this topic. In recent years the Grinnell Historical Museum has offered cemetery walks in the fall, an event where individuals are invited to come to the beautiful Hazelwood Cemetery and hear the stories of people who are buried there. When they learned that we were mapping the locations of all African Americans buried in Hazelwood was a part of our summer focus, they asked if we would be willing to share at this event. So that is how it happened that Tamara and I, along with Hemlock Stanier, Libby Eggert, and Evie Caperton (all Grinnell College class of 2025) ended up spending 4 hours in the cemetery together on a blustery Saturday afternoon.

We each told the story of one person. A map showing the locations and brief biographical information of the other 27 individuals we learned about was provided. The first story, told by Evie, was of the first Black Grinnellian. A man named Edward Delaney who arrived in 1854, the year Grinnell was founded. He chose to come with the family who had enslaved him his entire life. Evie did a beautiful job walking listeners through what is known and what can only be pondered about the bond they shared, which ended in his burial next to the family he had served all his years.

Hemlock, Libby and I were in the same location for the afternoon because the three people we spoke of were all buried in the same plot. Mumford Holland is buried next to Eliza Jane Craig, Edith’s grandmother. I told the story of George Craig, Edith’s grandfather, who is actually buried in an unmarked grave at the state hospital where he died, but whose spirit surely lies with his family here. His story is deeply interwoven with Grinnell history, going back to his escape to freedom via the Underground Railroad when he stopped in Grinnell in 1859 in a group that travelled with John Brown.

It was profoundly moving to sit and hear Hemlock and Libby tell these stories to individuals who came through. Hemlock, who has ties to the Quaker community through the high school she attended, has done a beautiful job uncovering the story of Eliza Jane Craig. As a toddler, Eliza Jane was sent away from her parents, a woman named Jane and the white plantation owner with whom she had three children. When her father knew he was dying, he sent his children to a free state to be cared for by Quakers. Despite his pleas, their mother decided to stay with him until his death. Tragically, his family refused to honor his wish to free her after he died and she never saw her children again. Hemlock beautifully expressed how Eliza Jane carried her mother’s story, as she carried her name, across the plains to Iowa and eventually to Grinnell.

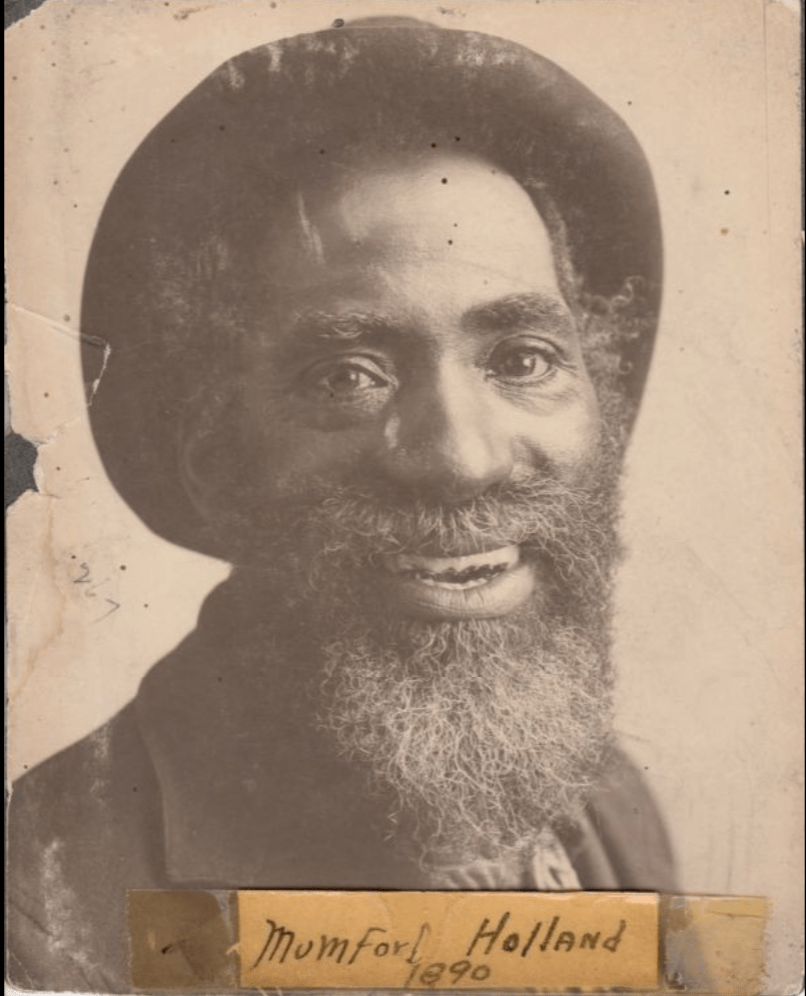

And then there was Mumford Holland. The portrait at the top of this post is from the library archives. It’s a striking picture that I have been aware of for years, but what was known about Mr. Holland was somewhat limited. Over the course of the summer we were able to fill in a bit more detail. He lived next door to George and Eliza Craig from nearly the time they moved to Grinnell in 1887. He was a property owner and offered space to rent and was in fact the landlord to Eva Pearl and Lee Renfrow before they bought a house of their own. A widower with no children, the family cared for him in his old age and he in turn left them what property he had at his death. And when that time came, he was buried in the family plot at Hazelwood.

At the top of this post I shared the last paragraph of Libby’s talk, where she envisions Mr. Holland, over 100 years at the time, holding the young Edith Renfrow, and imaging the life she might have. Could he ever have imagined all that has happened to bring us to the point that a building in town will now carry her family name?

Edith Renfrow Smith is a direct link to African Americans who came to this town as early as 1859. Her roots run through the very heart of the story of Grinnell as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Names of her family members are spread across decades of newspaper editions and public records. Her parents and siblings, her grandparents and aunts and uncles, her neighbors and friends, they walked these streets and experienced life in this town, with all the good and the bad and sad and the mad that life entails.

Their stories are being told again in this community. Their spirits live on and offer us lessons that call for humility and understanding. We will never fully understand what it was like for them. It is too foreign to our experience to imagine. Just as the current reality of a building that will be named Renfrow Hall would have been beyond what they could imagine.

If only they could see her now.

Leave a comment